THE JIM MORRISON MEMORIAL TELEPHONE

The Late Doors’ Singer Visited Atlanta in 1969

Stomp & Stammer/November, 2001

by

Jeff Calder

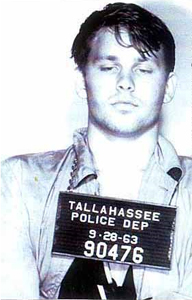

Two years prior to his Paris exit on July 3, 1971, Jim Morrison visited Atlanta with his friend, the photographer, Frank Lisciandro. It was June, 1969—three months after the Miami bust--and Morrison was here to receive recognition from The Atlanta International Film Festival for his 40-minute quasi-documentary on The Doors, Feast of Friends. The prize was called The Golden Phoenix Award, and, perhaps because of the gilded statue’s extravagant dimension, festival promoters enjoyed referring to it privately as “The Golden Penis Award.”

Screenings for the well-attended event were held that year at The High Museum. In addition to the Morrison short, the festival featured the Lenny Bruce cartoon, “Thank You, Masked Man,” as well as films by George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, whose quantities were not yet known. (The film-school version of Lucas’ THX 1138 was a last minute inclusion; Spielberg received a citation for his short submission, “Amblin’,” the name later assumed by his production company.)

J. Hunter Todd was the driving force behind the now-defunct Atlanta festival. It ran from 1968 to 1974, when, he says, the organization lost its financial support due to a citywide “real estate crash” and the subsequent bankruptcy of its main sponsor. With his keen eye for the main chance, Todd had the idea to import The Doors’ controversial singer; surprisingly, Morrison accepted. In Frank Lisciandro’s An Hour of Magic, a photojournal published in 1982 about his experiences with Morrison, the following excerpt can be found under a chapter concerning their two-day escapade in Atlanta:

“At the Festival headquarters we were greeted by Mr. J. Hunter Todd, the head honcho, who was delighted, even thrilled, to have Jim to show off. Jim and I were equally delighted with Hunter’s attaché case which contained a built-in mobile phone, the first we had ever seen. Jim had to try it, placing calls to L.A. (no one was in), and to an Atlanta D.J. Jim asked him to please announce the next day’s showing of Feast of Friends. The D.J. immediately put Jim on the air to make the announcement himself via the mobile phone.”

Today, J. Hunter Todd presides over the Worldfest-Houston International Film Festival, where he reigns daily as chief raconteur-in-charge. When contacted, Todd was unfamiliar with Lisciandro’s Atlanta account, though he confirmed that he still maintains possession of the antique telephone attaché.

“I still have it because it is such a monument! Occasionally people will show me their tiny Nokia, and I’ll say, ‘That’s not a phone. This is a phone.’ It cost about $3,000. Now you can get one for a penny. A very handsome leather black briefcase, normal size, but about six inches thick. Of course, it did stretch the limits of portability. I mean, you knew you were carrying the briefcase. Probably weighs 25 pounds! There is only enough room in the lid for your papers. The entire bottom is four inches of electronics. It’s the very phone that Jim Morrison called up the radio station on. I remember them being blown away by it. Even in Hollywood they didn’t have that. It’s in my closet at home. I’ll take it out tonight and fondle the handshaft.”

In his capacity as fundraiser for the Atlanta International Film Festival, J. Hunter Todd often met potential backers in boardrooms and bank offices around the city.

“I had a German assistant—tall, blond-- who would call me whenever I had a meeting. I would be there with my briefcase, you know, under the table. At a prearranged time she would give me a buzz. The briefcase would ring, and I would say to these important folks from some bank, ‘Oh, excuse me, I have a call.’ Then I would pick up that massive leather briefcase, open the top, revealing a flashing phone. I want you to know that presidents of the bank would sit there and freak out. They didn’t believe it was really real. I always got the money. Those were the days!”

In 1969, there were only three mobile channels in Atlanta: A, B and C.

“Only three people in the entire city could be talking [at one time]. If you wanted to make a call, the first thing you would do was press Channel A, and see if anybody was talking. And then if they were-- you’d listen! I would hear things that were too hot for my young ears. It still works. You have to put new batteries in it, but I picked it up recently, and the same channels that were dedicated to it then, are now.”

Todd believes he probably heard about “Feast of Friends” playing at a European Film Festival, though it had already premiered in Los Angeles before its showing at the High Museum. “It went like wildfire throu g h the town that he was actually at the film festival.

We screened it a Symphony Hall, which has 2,000 seats, and we had to call the police. We didn’t know about ticket control then. And we probably had 4,000 people who all had tickets. Cause naturally you sell tickets, and you also give away tickets, to your sponsors. Well, they all showed up that night. We managed to ace it by promising another show at midnight.”

Frank Lisciandro wrote that Morrison took advantage of the Atlanta invitation primarily to escape from his West Coast routine. Also, the consequences of his brush with the law in Florida were hanging over his head, a circumstance that dogged him till his death.

“We took [Morrison] out to the spots,” recalls Todd. “He wanted to see the town, and I was just so thrilled that he was there. Ted Turner was an old buddy then. An Unguided Missile! I remember we got together with Ted, which was a hoot. You know, The Big Mouth of The South. He might have just acquired WTBS, it was just a station, not the Superstation. It was an outrageous situation. I remember they were sort of volatile characters, to say the least. But it was good. We took [Morrison] to a fancy French restaurant, which has since disappeared [Chateau Fleur-de-lis on Cheshire Bridge], the scene of many epic encounters with Turner and I.”

In Lisciandro’s chronicle, after the High screening, Morrison and he wandered around the Hippie/Dope Strip, which, in 1969, was centered at Peachtree Road and 14th Street. They were invited to a party at a Victorian house where “Jim was treated with universal reverence.” Morrison pitched in $20 for booze and even helped prepare snacks in the kitchen.

The next night at the Hyatt Regency Hotel, however, the Awards Ceremony was an uptight tuxedo scene, which Jim tried to smooth by ordering six bottles of Pouilly-Fuisse for the table and cracking jokes. Lisciandro remembers a woman asking, “Where are you young men from?”

“ ‘From the top, ma’am,’ Jim said, pointing his finger and lifting his eyes.”

Morrison was bombed by the time he was presented the award by a young woman on the dais. In exchange for The Golden Phoenix, Morrison slipped her his room key.

In J. Hunter Todd’s memory, “Morrison was hilarious. Just out of control all the time, but in control, if you know what I mean. I was so impressed, because I had only known his persona from The Doors, so to see him as a filmmaker and a guy there to promote the movie was kind of astounding. As I recall, he was wearing something different almost every hour. Nothing tweedy, though.”